From Whence Subject Matter?

|

| Pears drawn with pencil, white charcoal pencil on pastel paper |

If you wanted to learn a new skill, what would you do? Take a class? Go to the library? Look for online classes? Of course! Would you expect to know all about the subject matter before teaching began? Of course not!

Why then do people expect to know how to draw or paint before the first class? I’ve had students “practice” before class because they didn’t want to look stupid. Others talk about not having “talent” so they won’t venture to try. Quite a few of my junior high students would say upon entering the classroom, “No one in my family can draw a straight line without a ruler.”

My responses in order: If you’re supposed to know all about a class before the first meeting, what exactly is my role? If you think that you have to be imbued with TALENT to participate, please read my earlier blog, “Who gets the Creative Gene?” And about rulers and straight lines? I told the kids that straight lines were boring so they would be fine.

For this blog, I’ll confine my comments to drawing and how I approach it. Here is the deal, drawing is not magic, nor is it limited to those talented few. It is a learned skill that can provide years of enjoyment with limited materials and reasonable cost. The more you draw the better you will be. That is a certainty.

When you first begin to draw, do yourself a favor and look for subject matter that fits these three criteria – choose a simple shape; pick a familiar form; draw from life, not a photo. By beginning with a simple, recognizable shape, you go far in establishing a sucessful drawing experience. Once you master simple shapes, more complex ones will seem easier to tackle. By drawing from life, you can touch and smell as well as see your subject. The opportunity to look at various positions and views allows you to choose the most pleasing to you. Photographs do not allow this intense scrutiny and the varying angles are not available. Being familiar with your subject is a real bonus when drawing. If you work with shapes you have seen for years you don’t have to spend time learning unusual aspects of your subject.

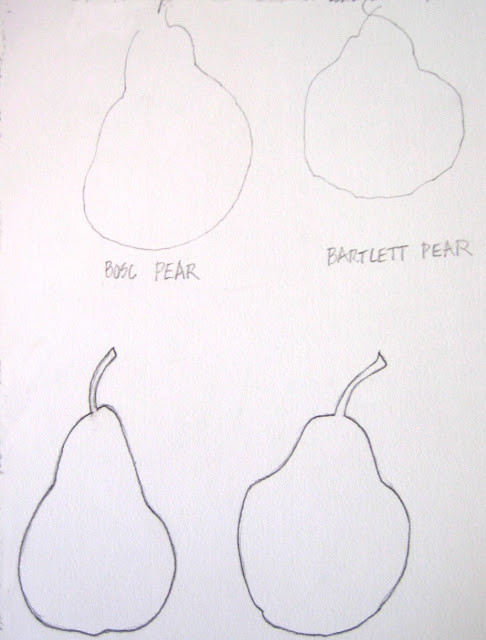

The drawing described here will be natural forms. I have illustrated the pear for the examples shown but you can just apply these suggestions to another still life subject. I used two different pears, a Bartlett and a Bosc. There is nothing special about my choice as many would suffice, but I find the pear shape to be beautiful and graceful, hence the choice.

DRAWING CONTOURS

The contour of a shape describes the edge of form. Think of the shape as a silhouette – you will draw the edge of that silhouette. Learning to do a contour drawing is essential for painting. Often I am attracted to a subject but until I do a simple contour drawing, adjusting the image to my liking, I don’t really know if it will work. Often I do several of these small thumbnail drawings to see what arrangement is the best.

|

| Top row: Blind Contour Bottom row: Pure Contour |

When you are first beginning to draw, the blind contour will encourage your close attention. This is all about training your hand to draw what your eye sees. Place your pencil on the paper and draw the contour without again looking at your paper until you have finished the form. This is not a race and you’ll be more observant if you go slowly and carefully. Don’t worry if the drawing is a bit wacky – you’re goal is to really, truly look at the shape.

Pure Contour: Draw the same object you used for the first exercise. This time, place your pencil on the paper and draw the shape while looking back and forth as much as needed. Go slowly and keep your pencil firmly on the page. The line should be continuous and not sketchy.

|

||

| Bartlett Pear |

|

| Bosc Pear |

The Bartlett pear (above) was just about as wide as it was tall. When I measured with my pencil I compared the height to the width. In this case the measurement was very similar however that may not always be the case. The Bosc pear was about 1 1/3 times taller than it was wide. Notice the slope of the “shoulder” of the fruit. After you have an accurate contour drawing, which should do much to describe your subject, you may begin to add shading or value.

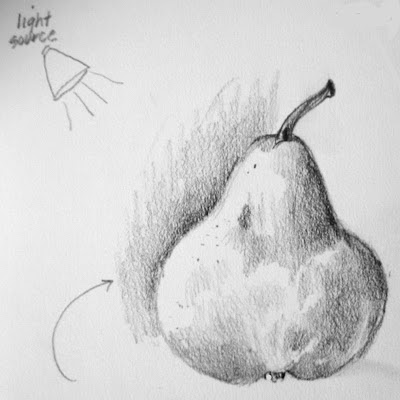

ADDING SHADOWS

The addition of shadows will change your flat contour drawing into a seemingly 3-dimensional object. To see the shadows, shine a light on the subject to create a shadowed side. An old desk lamp will do but you do need a light fairly close to the subject so sharp contrasts are visible. To enhance your observation, squint your eyes almost shut and the darks and lights will be obvious. By adjusting the pressure on the pencil lead, a range of values, or grays, can be created. Add the details of stem, bud end, bruises and texture as needed.

By shadowing the background on the light side of the pear, it appears lighter and stands out from the background.

After I drew the pear from one angle, I went on to draw it from other views. Once you get to know a shape, draw it several times. Put that knowledge to use.

Remember, drawing is not magic. Anyone can do it with a bit of direction and time to practice. This is something you can enjoy for your entire life. The more drawing you do, the more observant you become and more skilled at replicating your subject. Now go out there and discover the wonderful, beautiful world – you will see it in a whole new way!

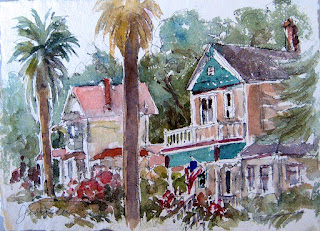

Watercolor Musings: The Value of Asking “What If”: …and the importance of building personal scaffolds Early Bak ersfield School House Recently I had a fascinating conver…

|

| Early Bakersfield School House |

Recently I had a fascinating conversation with my sister who after retiring from the classroom is presenting at conferences for teachers. We come from a long line of educators going back to our grandfather who graduated from Bowdoin College in Maine in 1900 and after being a teacher and principal finished his career as Superintendent of Schools in Redlands California. Most of our family’s four generations of educators taught in grades K-6, but since my credential was a Special Secondary in Art, I had a different group of classes than those teaching elementary school. As my sister was describing her new training, she also mentioned “scaffolding,” a term I was unfamiliar with in the classroom setting. She said it’s the concept of the teacher presenting material just a bit ahead of each student’s level, encouraging growth smoothly from one building block to another.

| Some favorite supplies |

Robert E Wood, a fine watercolorist and teacher gave one of the best pieces of advice I’ve ever gotten from a workshop leader. He admonished us to keep ourselves on the edge of comfort, approaching discomfort, to refrain from painting the “same painting over and over.” By focusing on a few goals to solve in the creative process, the learning expands and quality improves because the artist is actively solving problems rather than painting “pretty pictures.”

Watercolor Musings: Learning from Robert E. Wood: Robert E. Wood (1926-1999) was known for his watercolor landscapes, marine paintings and figures in a semi-abstract style. He earned …

|

|||

| Taxco by Robert E. Wood |

|

| Figure by Robert E. Wood |

|

||

| Mosaic by Millard Sheets in the former Home Savings and Loan Tower in Pomona |

I was extremely fortunate to study with Millard Sheets in his final two workshops. I kept copious notes and from them extracted tips and admonitions on color and value. These have been very helpful for me and I’m happy to pass them along.

Watercolor Musings: Mom Was Right, Say Thank You: It was the best car my 8-year-old self could have wished for…a 1949 Ford Convertible in yellow! The first of only two new cars my …

|

|

| FORD TIMES – January 1953, June 1956, April 1957 |

Watercolor Musings: Benefits for New Painters – Ink & Watercolor: Old Oak, Paso Robles All the images in this post were published in “Work Small, Learn Big!” published in 2003 by International…

|

| Old Oak, Paso Robles |

|

| The Courtyard, Orange |

|

| Vine Street Victorians, Paso Robles |

It keeps you focused. By working quickly, you’ll be more inclined to concentrate on big shapes and really, truly observe the environment.

It makes you practice drawing. Starting with pen, not pencil, is a huge boost. Unable to second guess yourself once the pen touches the paper, you’ll keep drawing even though corrections need to be made along the way.

It helps you get over perfectionism. When the waterolor is added, some of the drawing lines are blurred so “making it perfect” is no longer a concern.

|

| Coffee Corner, Orange |

It builds confidence quickly. The more you do the better you get, period. And that leads to more work which, in turn, gets better and better.

It reduces your stress level. It’s the kind of fun that takes complete concerntration. You can’t worry about anything when you’re so happily engaged in painting.

It keeps you young by engaging the mind and body and teaching you to see the world differently. And the decision making that must be done as you work exercises the brain. I’ve always thought that Ponce de Leon, that seeker of the fountain of youth, had it half right. Not only water is necessary, but so in paint!

Watercolor Musings: Who gets the “Creative Gene?”: Santa Barbara Mission in pencil and paint. I suspect my affinity for watercolor has lots to do with my love of drawing. I began drawing at…

Watercolor Musings: Designing Images with Meaning – II: This is a continuation of the initial blog about designing images with meaning. These creative problems are fun to do and I usuall y “thro…

This is a continuation of the initial blog about designing images with meaning, in this case those created for the Orange Public Library History Walk. These creative problems are fun to do and I usually “throw” the requirements in the back of my head and let it simmer for awhile. The idea of the images was to tell the story of the city of Orange within images and a brief text by Phil Brigandi. The following are the stories of the railroad, citrus industry and agriculture that was NOT citrus.

|

| The Railroad |

|

||

| The Citrus Industry |

|

||

| Early Agriculture |